Cyrus the Great's Charter of Human Rights

Introduction

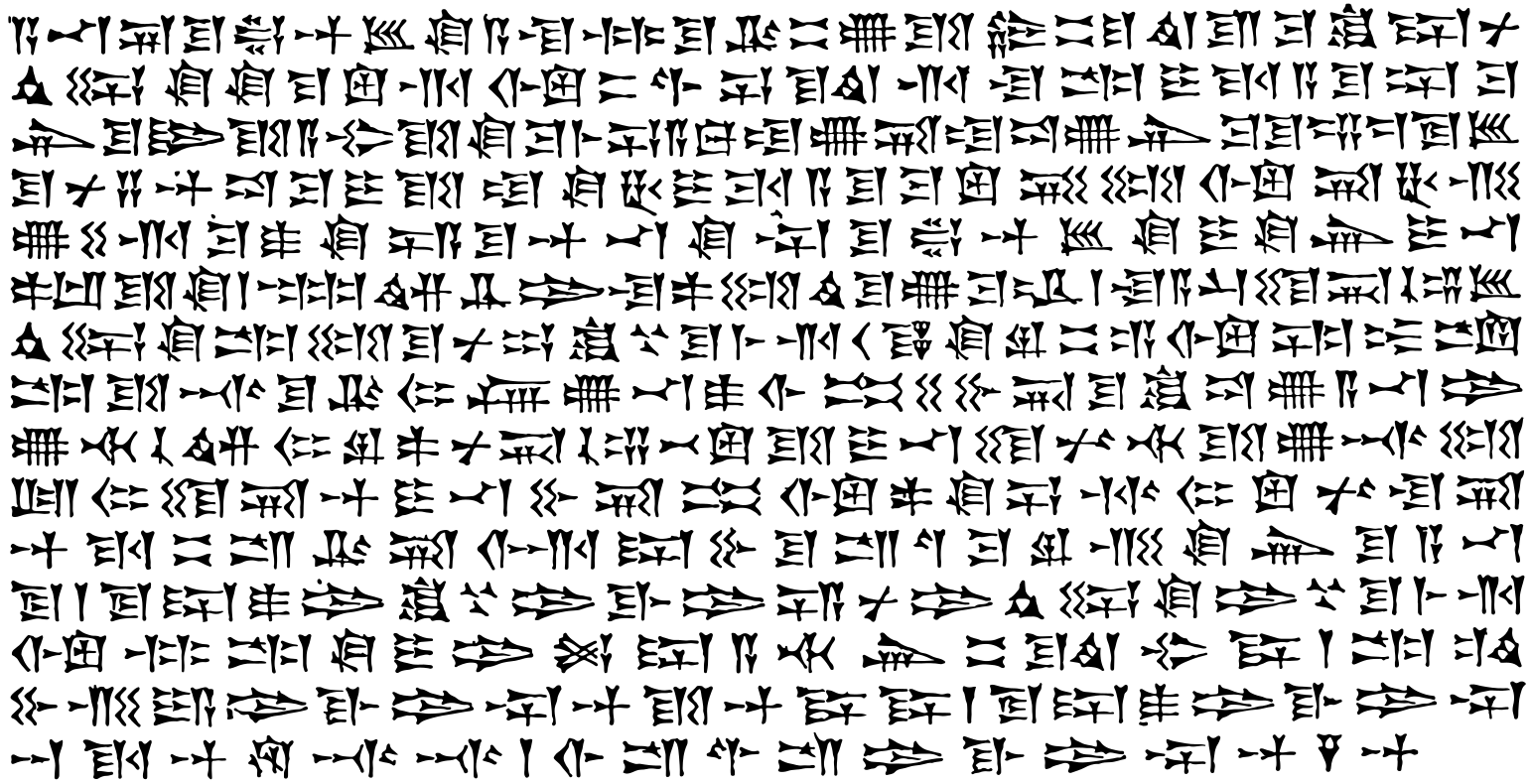

The Cyrus cylinder is a fragmentary clay cylinder with an Akkadian inscription of thirty-five lines discovered in a foundation deposit by Hormuzd Rassam, a 19th century Assyriologist, during his excavations at the site of the Marduk temple in Babylon in 1879. A second fragment, containing lines 36-45, was identified in the Babylonian collection at Yale University by PR Berger. The total inscription, though incomplete at the end, consists of forty-five lines, the first three almost entirely broken away.

The text contains an account of Cyrus the Great’s conquest of Babylon in 539 BC, beginning with a narrative of the crimes of Nabonidus, the last Chaldean king (lines 4-8). Then follows an account of Marduk’s search for a righteous king, his appointment of Cyrus to rule all the world, and his causing Babylon to fall without a battle (lines 9-19). Cyrus continues in the first person, giving his titles and genealogy (lines 20-22) and declaring that he has guaranteed the peace of the country (lines 22-26), for which he and his son Cambyses have received the blessing of Marduk (lines 26-30). He describes his restoration of the cult, which had been neglected during the reign of Nabonidus, and his permission to the exiled peoples to return to their homeland (lines 30-36). Finally, the king records his restoration of the defenses of Babylon (lines 36-43) and reports that in the course of the work he saw an inscription of Ashurbanipal (lines 43-45).

The text was actually composed by priests of Marduk, in an archaising form inspired by Neo-Assyrian models, particularly inscriptions of Assurbanipal (668-27 B.C.E.) drafted in Babylon (Harmatta). The cylinder thus contains a typical Mesopotamian building inscription placed as a foundation deposit in the walls of Babylon to commemorate Cyrus’ restorations there.

Why the Cyrus the Great's Cylinder is important?

The Cyrus Cylinder has a cross-cultural significance and been internationally recognised as a symbol of tolerance and freedom. The cylinder was first described as “the world’s first charter of human rights” in late 1960s by the Shah of Iran. Later on, in 1971, a replica of the cylinder was presented by HIH Princess Ashraf Pahlavi, on behalf of the government of Iran, to the United Nations (ref: UN Correspondence Files). The replica is kept at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, on the second floor hallway. Since then, the United Nations continues to promote the cylinder as “an ancient declaration of human rights”.

Although a number of scholars debate the idea of relating the cylinder to the human rights, the facts that 2,500 years ago, a powerful man set the people free, let the captives go back to their homeland and rebuild their temple, and respected the other religions are undeniable. Such contrast on tolerance and freedom is especially significant within a historical era with absolutely no mindset on the humanitarianism concepts. To compare, less than a hundred years before Cyrus the Great and in a dramatic contrast, the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal described his invasion to Susa as:

Susa, the great holy city, abode of their gods, seat of their mysteries, I conquered. I entered its palaces, I opened their treasuries where silver and gold, goods and wealth were amassed... I destroyed the ziggurat of Susa. I smashed its shining copper horns. I reduced the temples of Elam to naught; their gods and goddesses I scattered to the winds. The tombs of their ancient and recent kings I devastated, I exposed to the sun, and I carried away their bones toward the land of Ashur. I devastated the provinces of Elam and on their lands I sowed salt.

Last but not least, it is worth to mention the founding fathers of the United States sought inspiration from Cyrus, what he did in Babylon as described by the Cyrus Cylinder, and how he ran a country. Thomas Jefferson owned two personal copies of Xenophon’s book Cyropaedia – the Education of Cyrus – which was “a mandatory read for statesmen.”

What the British Museum says about the cylinder?

English translation of the cylinder

[When …] … [… wor]ld quarters […] … a low person was put in charge of his country, but he set [a (…) counter]feit over them. He ma[de] a counterfeit of Esagil [and …] … for Ur and the rest of the cult-cities. Rites inappropriate to them, [impure] fo[od- offerings …] disrespectful […] were daily gabbled, and, intolerably, he brought the daily offerings to a halt; he inter[fered with the rites and] instituted […] within the sanctuaries. In his mind, reverential fear of Marduk, king of the gods, came to an end. He did yet more evil to his city every day; … his [people…], he brought ruin on them all by a yoke without relief. Enlil-of-the-gods became extremely angry at their complaints, and […] their territory. The gods who lived within them left their shrines, angry that he had made them enter into Babylon (Shuanna). Ex[alted Marduk, Enlil-of-the-Go]ds, relented. He changed his mind about all the settlements whose sanctuaries were in ruins and the population of the land of Sumer and Akkad who had become like corpses, and took pity on them. He inspected and checked all the countries, seeking for the upright king of his choice. He took under his hand Cyrus, king of the city of Anshan, and called him by his name, proclaiming him aloud for the kingship over all of everything. He made the land of the Qutu and all the Medean troops prostrate themselves at his feet, while he looked out in justice and righteousness for the black-headed people whom he had put under his care. Marduk, the great lord, who nurtures his people, saw with pleasure his fine deeds and true heart and ordered that he should go to Babylon He had him take the road to Tintir, and, like a friend and companion, he walked at his side. His vast troops whose number, like the water in a river, could not be counted, marched fully-armed at his side. He had him enter without fighting or battle right into Shuanna; he saved his city Babylon from hardship. He handed over to him Nabonidus, the king who did not fear him. All the people of Tintir, of all Sumer and Akkad, nobles and governors, bowed down before him and kissed his feet, rejoicing over his kingship and their faces shone. The lord through whose trust all were rescued from death and who saved them all from distress and hardship, they blessed him sweetly and praised his name.

I am Cyrus, king of the universe, the great king, the powerful king, king of Babylon, king of Sumer and Akkad, king of the four quarters of the world, son of Cambyses, the great king,, king of the city of Anshan, grandson of Cyrus, the great king, ki[ng of the ci]ty of Anshan, descendant of Teispes, the great king, king of Anshan, the perpetual seed of kingship, whose reign Bel and Nabu love, and with whose kingship, to their joy, they concern themselves.

When I went as harbinger of peace i[nt]o Babylon I founded my sovereign residence within the palace amid celebration and rejoicing. Marduk, the great lord, bestowed on me as my destiny the great magnanimity of one who loves Babylon, and I every day sought him out in awe. My vast troops marched peaceably in Babylon, and the whole of [Sumer] and Akkad had nothing to fear. I sought the welfare of the city of Babylon and all its sanctuaries. As for the population of Babylon […, w]ho as if without div[ine intention] had endured a yoke not decreed for them, I soothed their weariness, I freed them from their bonds(?). Marduk, the great lord, rejoiced at [my good] deeds, and he pronounced a sweet blessing over me, Cyrus, the king who fears him, and over Cambyses, the son [my] issue, [and over] my all my troops, that we might proceed further at his exalted command. All kings who sit on thrones, from every quarter, from the Upper Sea to the Lower Sea, those who inhabit [remote distric]ts (and) the kings of the land of Amurru who live in tents, all of them, brought their weighty tribute into Shuanna, and kissed my feet. From [Shuanna] I sent back to their places to the city of Ashur and Susa, Akkad, the land of Eshnunna, the city of Zamban, the city of Meturnu, Der, as far as the border of the land of Qutu - the sanctuaries across the river Tigris - whose shrines had earlier become dilapidated, the gods who lived therein, and made permanent sanctuaries for them. I collected together all of their people and returned them to their settlements, and the gods of the land of Sumer and Akkad which Nabonidus – to the fury of the lord of the gods – had brought into Shuanna, at the command of Marduk, the great lord, I returned them unharmed to their cells, in the sanctuaries that make them happy. May all the gods that I returned to their sanctuaries, every day before Marduk and Nabu, ask for a long life for me, and mention my good deeds, and say to Marduk, my lord, this: “Cyrus, the king who fears you, and Cambyses his son, may their … […] […….].” The population of Babylon call blessings on my kingship, and I have enabled all the lands to live in peace. Every day I copiously supplied [… ge]ese, two ducks and ten pigeons more than the geese, ducks and pigeons […]. I sought out to strengthen the guard on the wall Imgur-Enlil, the great wall of Babylon, and […] the quay of baked brick on the bank of the moat which an earlier king had bu[ilt but not com]pleted, [I …] its work. [… which did not surround the city] outside, which no earlier king had built, his troops, the levee from his land, in/to Shuanna. […] with bitumen and baked brick I built anew, and completed its work. […] great [doors of cedarwood] with copper cladding. I installed all their doors, threshold slabs and door fittings with copper parts. […] I saw within it an inscription of Ashurbanipal, a king who preceded me, […] … […] … [… for] ever.

Acknowledgement

The English translation of the cylinder is by Irving Finkel, Curator of Cuneiform Collections at the British Museum. It was sourced from the British Museum website accessed online on 20 June 2019.

References and further sources

This article is sourced from:

Also, the following further sources are recommended:

Let's interact!